Introduction to Multicore Computing

Multicore Processor

- A single computing component with two or more independent cores

- Core: computing unit that reads / executes program instructions

- Multiple cores run multiple instructions at the same time (concurrently)

- Increase overall program speed (performance)

- performance gained by multi-core processor

- desktop PCs, mobile devices, servers

Manycore processor (GPU)

- multi-core architectures with an especially high number of cores (thounds)

- CUDA

- Compute Unified Device Architecture

- OpenCL

Thread / Process

- Both: independent sequence of execution

- Process: run in seperate memory space

- Thread

- run in shared memory space in a process

- One process may have multiple threads

- Multithreaded Program

- a program running with multiple threads that is executed simultaneously

What is Parallel Computing?

- Parallel computing

- using multiple processors in parallel to solve problems more quickly than with a single processor

- Examples of parallel machines:

- A cluster computer that contains multiple PCs combined together with a high speed network

- A shared memory multiprocessor by connecting multiple processors to a single memory system

- A chip Multi-Processor (CMP) contains multiple processors (called cores) on a single chip

- Concurrent execution comes from desire for performance; unlike the inherent concurrency in a multi-user distributed system

Parallelism vs Concurrency

- Parallel Programming

- Using additional computational resources to produce an answer faster

- Problem of using extra resources effectively?

- Ex. summing up all the numbers in an array with multiple n processors

- Concurrent Programming

- Correctly and efficiently controlling access by multiple threads to shared resources

- Problem of preventing a bad interleaving of operations from different threads

- Example

- Implementation of dictionary with hashtable

- operations insert, update, lookup, delete occur simultaneously (concurently)

- Multiple threads acceess the same hashtable

- Web Visit Counter

- Implementation of dictionary with hashtable

- Often used interchangeably

- In practice, the distinction between parallelism and concurrency is not absolute

- Many multithreaded programs have aspects of both

Parallel Programming Techniques

- Shared Memory

- OpenMP, pthreads

- Distributed Memory (several computer 로 나눠지지만, processor 는 다른 컴퓨터의 memory 에 직접 접근하지는 못함)

- MPI

- Distributed / Shared Memory (Share memory 를 가지고 있지만, 직접 접속은 할 수 없음)

- Hybrid (MPI + OpenMP)

- GPU Parallel Programming

- CUDA Programming

- OpenCL

Parallel Processing Systems

- Small-Scale Multicore Environment

- Notebook, Workstation, Server

- OS supports multicore

- POSIX threads (pthread), win32 thread

- GPGPU-based supercomputer

- Development of CUDA/OpenCL/GPGPU

- Large-Scale Multicore Environment

- Supercomputer: more than 10000 cores

- Clusters

- Servers

- Grid Computing

Parallel Computing vs Distributed Computing

- Parallel Computing

- all processors may have access to a shared memory to exchange information between processors.

- more tightly coupled to multi-threading

- Distributed Computing

- multiple computers communicate through network

- each processor has its own private memory (distributed memory)

- executing sub-tasks on different machines and then merging the results. (Each computer has a sub-result)

- Distributed 는 parallel 의 한 종류이다.

- No Clear Distinction

Cluster Computing vs Grid Computing

- Cluster Computing

- a set of loosely connected computers that work together so that in many respects they can be viewed as a single system

- good price / performance

- memory not shared

- Grid Computing

- federation of computer resources from multiple locations to reach a common goal (a large scale distributed system)

- grid tend to be more loosely coupled, heterogeneous, and geographically dispersed

Cloud Computing

- shares networked computing resources rather than having local servers or personal devices to handle applications

- “Cloud” is used as a metaphor for “Internet” meaning “a type of Internet-based computing”

- different services - such as servers, storage and applications - are delivered to an user’s computers and smart phones through the Internet.

Good Parallel Program

- Writing good parallel programs

- Correct

- Good Performance

- Scalability

- Load Balance

- Portability

- Hardware Specific Utilization

Characteristics of Distributed System

- Resource Sharing: It is the ability to use any Hardware, Software, or Data anywhere in the System.

- Openness: It is concerned with Extensions and improvements in the system (i.e., How openly the software is developed and shared with others)

- Concurrency: It is naturally present in Distributed Systems, that deal with the same activity or functionality that can be performed by separate users who are in remote locations. Every local system has its independent Operating Systems and Resources.

- Scalability: It increases the scale of the system as a number of processors communicate with more users by accommodating to improve the responsiveness of the system.

- Fault tolerance: It cares about the reliability of the system if there is a failure in Hardware or Software, the system continues to operate properly without degrading the performance of the system

- Transparency: It hides the complexity of the Distributed Systems to the Users and Application programs as there should be privacy in every system.

- Heterogeneity: Networks, computer hardware, operating systems, programming languages, and developer implementations can all vary and differ among dispersed system components.

Challenges of Distributed Systems

- Network latency: The communication network in a distributed system can introduce latency, which can affect the performance of the system.

- Distributed coordination: Distributed systems require coordination among the nodes, which can be challenging because of the distributed nature of the system.

- Data consistency: Maintaining data consistency across multiple nodes in a distributed system can be challenging.

Advantages

- High Performance a. Distributed systems can outperform centralised systems by utilising the capabilities of several computers to handle the demand.

- Reliable a. In terms of failures, distributed systems are significantly more dependable than single systems. Even if a single node fails, it does not affect the remaining servers. Other nodes can continue to operate normally.

- Scalable

- Expandability

- Availability

- Reduced latency (short distance) a. Low latency is achieved using distributed systems. If a node is closer to the user, the distributed system ensures that traffic from that node reaches the system. As a result, the user may realise that it takes significantly less time to serve them.

- Secure a. Distributed systems include security safeguards that prevent data breaches and illegal access to any data, hardware or software of an organization.

- Cost-effectiveness a. Distributed systems, despite their high expense of implementation, are reasonably cost-effective in the long term. In contrast to a mainframe computer, which is made up of multiple processors, a distributed system is made up of several computers working together. This infrastructure is significantly less expensive than a mainframe system.

- Geographic Distribution a. A feature of a distributed system is geographic distribution. It allows companies and organisations to provide users with services in different areas.

Disadvantages

- High cost.

- The problem is finding the fault.

- More space is needed.

- The increased infrastructure is needed.

- In distributed systems, it is challenging to provide adequate security because both the nodes and the connections must be protected.

Moore’s Law: Review

- Doubling of the number of transistors on integrated circuits roughly every two years.

- Microprocessors have become smaller, denser, and more powerful.

- processing speed, memory capacity, sensors and even the number and size of pixels in digital cameras. All of these are improving at (roughly) exponenetial rates

Computer Hardware Trend

- Chip density is continuing increase ~2x every 2years

- Clock speed is not increasing anymore (in high clock speed, power consumption and heat generation is too high to be tolerated)

- number of cores may double instead

- No more hidden parallelism to be found

- Transistor number still rising

- Clock speed flattening sharply.

=> Need Multicore programming!

- All computers are now parallel computers.

- Multi-core processors represent an important new trend in computer architecture.

- Decreased power consumption and heat generation

- Minimized wire lengths and interconnect latencies.

- They enable tru thread-level parallelism with great energy efficiency and scalability.

Why writing (fast) parallel programs is hard

Principles of Parallel Computing

- Finding enough parallelism (Amdahl’s Law)

- granularity

- Locality

- Load balance

- Coordination and synchronization

→ All of these things makes parallel programming even harder than sequential programming

Finding Enough Parallelism

- Suppose only part of an application seems parallel

- Amdahl’s law

- let s be the fraction of work done sequentially, so (1-s) is fraction parallelizable

- P = number of processors

- Even if the parallel part speeds up perfectly performance is limited by the sequential part

Overhead of Parallelism

- Given enough parallel work, this is the biggest barrier to getting desired speedup

- Parallelism overheads include:

- cost of starting a thread or process

- cost of communicating shared data

- cost of synchronizing

- extra (redundant) computation

- Each of these can be in the range of milliseconds (=millions of flops) on some systems

- Tradeoff: Algorithm needs sufficiently large units of work to run fast in parallel, but not so large that there is not enough parallel work

Locality and Parallelism

- Large memories are slow, fast memories are small

- Storage hierarchies are large and fast on average

- Parallel processors, collectively, have large, fast cache

- the slow accesses to “remote” edata we call “communication”

- Algorithm should do most work on local data

Load imbalance

- Load imbalance is the time that some processors in the system are idle due to

- insufficient parallelism (during that phase)

- unequal size tasks

- Algoroithm needs to balance load

Hyper-threading

- Hyper-threading is Intel’s proprietary simultaneous multithreading implementation used to improve parallelization of computations (doing multiple tasks at once) performed on x86 microprocessors.

Performance of Parallel Programs

Flynn’s Taxonomy on Parallel Computer

- Classified with two independent dimension

- Instruction stream

- Data stream

SISD (Single Instruction, Single Data)

- A serial (non-parallel) computer

- This is the oldest and even today, the most common type of computer

SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data)

- All processing units execute the same instruction at any given clock cycle

- Best suited for specialized problems characterized by a high degree of regularity, such as graphics/image processing

MISD (Multiple Instruction, Single Data)

- Each processing unit operates on the data independently via separate instruction streams

- Few actual examples of this class of parallel computer have ever existed.

MIMD (Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data)

- Every processor may be executing a different instruction stream

- Every processor may be working with a different data stream

- the most common type of parallel computer

- Most modern supercomputers fall into this category

Creating a Parallel Program

- Decomposition

- Assignment

- Orchestration/Mapping

Decomposition

- Break up computation into tasks to be divided among processes

- identify concurrency and decide level at which to exploit it

Domain Decomposition

- Data associated with a problem is decomposed.

- Each parallel task then works on a portion of data.

Functional Decomposition

- the focus is on the computation that is to be performed rather than on the data

- problem is decomposed according to the work that mulst be done.

- Each task then performs a portion of the overall work.

Assignment

- Assign tasks to threads

- Balance workload, reduce communication and management cost

- Together with decomposition, also called partitioning

- Can be performed statically, or dynamically

- Goal

- Balanced workload

- Reduced communication costs

Orchestration

- Structuring communication and synchronization

- Organizing data structures in memory and scheduling tasks temporally

- Goals

- Reduce cost of communication and synchronization as seen by processors

- Reserve locality of data reference (including data structure organization)

Mapping

- Mapping threads to execution units (CPU cores)

- Parallel application treis to use the entire machine

- Usually a job for OS

- Mapping decision

- Place related threads (cooperating threads) on the same processor

- maximize locality, data sharing, minimize costs of comm/sync

Performance of Parallel Programs

- What factors affect the performance?

- Decomposition

- Coverage of parallelism in algorithm

- Assignment

- Granularity of partitioning among processors

- Orchestration/Mapping

- Locality of computation and communication

- Decomposition

Coverage (Amdahl’s Law)

- Potential program speedup is defined by the fraction of code that can be parallelized

- speed up은 sequential work 의 비율에 달려있다.

Amdahl’s Law

- p = fraction of work that can be parallelized

- n = the number of processor

- s = 1-p

Implications of Amdahl’s Law

- Speeedup tends to 1/(1-p) as number of processors tends to infinity

- Parallel programming is worthwhile when programs have a lot of work that is parallel in nature

Performance Scalability

- Scalability: the capable of a system to increase total throughput under an increased load when resources (typically hardwares) are added

Granularity (work units)

- Granularity is a qualitative measure of the ratio of computation to communication

- Coarse: relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication events

- Fine: relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events

- Computation stages are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events

- Granularity

- the extent to which a system is broken down into small parts

- Coarse-grained systems

- consist of fewer, larger components than fine-grained systems

- regards large subcomponents

- Fine-grained systems

- regards smaller components of which the larger ones are composed

Fine vs Coarse Granularity

- Fine-grain Parallelism

- Low computation to communication ratio

- Small amounts of computational work between communication stages

- High communication overhead

- Coarse-grain Parallelism

- High computation to communication ratio

- Large amounts of computational work between communication events

- The most efficient granularity is dependent on the algorithm and the hardware

- In most cases the over head associated with communications and synchronization is high relative to execution speed so it’s advantageous to have coarse granularity.

- Fine-grain parallelism can help reduce overheads due to load imbalance.

Load Balancing

- distributing approximately equal amounts of work among tasks so that all tasks are kept busy all of the time.

- It can be considered a minimization of task idle time.

- For example, if all tasks are subject to a barrier syncrhonization point, the slowest task will determine the overall performance.

General Load Balancing Problem

- The whole work should be completed as fast as possible.

- As workers are very expensive, they should be kept busy.

- The work should be distributed fairly. About the same amount of work should be assigned to every worker.

- There are precedence constraints between different tasks (we can start building the roof only after finishing the walls) Thus we also have to find a clever processing order of the different jobs.

Load Balancing Problem

- Processors that finish early have to wait for the processor with the largest amount of work to complete

- Leads to idle time, lowers utilization

Static load balancing

- Programmer make decisions and assigns a fixed amount of work to each processing core a priority

- Low run time overhead

- Works well for homogeneous multicores

- All core are the same

- Each core has an equal amount of work

- Not so well for heterogeneous multicores

- Some cores may be faster than others

- Work distribution is uneven

Dynamic Load Balancing

- When one core finishes its allocated work, it takes work from a work queue or a core with the heaviest workload

- Adapt partitioning at run time to balance load

- High runtime overhead

- Ideal for codes where work is uneven, unpredictable, and in heterogeneous multicore

Granularity and Performance Tradeoffs

- Load balancing

- How well is work distributed among cores?

- Synchronization/Communication

- Communication Overhead?

Communication

- With message passing, programmer has to understand the computation and orchestrate the communication accordingly

- Point to Point

- Broadcast (one to all) and Reduce (all to one)

- All to All (each processor sends its data to all others)

- Scatter (one to several) and Gather (several to one)

Factors to consider for communication

- Cost of communications

- Inter-task communication virtually always implies overhead.

- Communications frequently require some type of synchronization between tasks, which can result in tasks spending time ‘waiting’ instead of doing work.

- Latency vs Bandwidth

- Latency

- the time it takes to send a minimal (0 byte) message from point A to point B

- Bandwidth

- the amount of data that can be communicated per unit of time.

- Sending many small messages can cause latency to dominate communication overheads

- Often it is more efficient to package small messages into a larger message.

- Latency

- Synchronous vs asynchronous

- Synchronous: require some type of handshaking between tasks that share data

- Asynchronous: transfer data independently from one another.

- Scope of communication

- Point-to-point

- collective

MPI: Message Paassing Library

- MPI: portable specification

- Not a language or compiler specification

- Not a specific implementation or product

- SPMD model (same program, multiple data)

- For parallel computers, clusters, and heterogeneous networks, multicores

- Multiple communication modes allow precise buffer management

- Extensive collective operations for scalable global communication

Point-to-Point

- Basic method of communication between two processors

- Originating processor “sends” messages to destination processor

- Destination processor then “receives” the message

- The message commonly includes

- Data or other information

- Length of the message

- Destination address and possibly a tag

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Messages

- Synchronous send

- Sender notified when message is received

- Asynchronous send

- Sender only knows that message is sent

Blocking vs Non-Blocking Messages

- Blocking messages

- Sender waits until message is transmitted: buffer is empty

- Receiver waits until message is received: buffer is full

- Potential for deadlock

- Non-blocking

- Processing continues even if message hasn’t been transmitted

- Avoid idle time and deadlocks

Broadcast

- One processor sends the same information to many other processors

- MPI_BCAST

Reduction

- Example: every processor starts with a value and needs to know the sum of values stored on all processors

- A reduction combines data from all processors and returns it to a single process

- MPI_REDUCE

- Can apply any associative operation on gathered data

- ADD, OR, AND, MAX, MIN, etc…

- No processor can finish reduction before each processor has contributed a value

- BCAST/REDUCE can reduce programming complexity and may be more efficient in some programs.

Synchronization

- Coordination of simultaneous events (threads / processes) in order to obtain correct runtime order and avoid unexpected condition

- Types of synchronization

- Barrier

- Any thread / process must stop at this point (barrier) and cannot proceed until all other threads / processes reach this barrier

- Lock/Semaphore

- The first task acquires the lock. This task can then safely (serially) access the protected data or code.

- Other tasks can attempt to acquire the lock but must wait until the task that owns the lock releases it.

- Barrier

Locality

- Algorithm should do most work on local data

- Need to exploit spatial and temporal locality

Locality of memery access (shared memory)

- Parallel computation is serialized due to memory contention and lack of bandwidth

- Distribute data to relieve contention and increase effective bandwidth

Memory Access Latency in Shared Memory Architectures

- Uniform Memory Access (UMA)

- Centrally located memory

- All processors are equidistant (access times)

- Non-Uniform Access (NUMA)

- Physically partitioned but accessible by all

- Processors have the same address space (Logically large one memory)

- Placement of data affects performance (멀리 떨어진 데이터는 접근할 때 많은 시간이 소요됨)

- CC-NUMA (Cache-Coherent NUMA)

Cache Coherence

- the uniformity of shared resource data that ends up stored in multiple local caches

- Problem: When a processor modifies a shared variable in local cache, different processors may have different value of the variable

- Copies of a variable can be present in multiple caches

- A write by one processor may not beccome visible to others

- They’ll keep accessing stale vaule in their caches

- Need to take actions to ensure visibility or cache coherence

- Snooping cache coherence

- Send all request for data to all processors

- Works well for small systems

- Directory-based cache coherence

- Keep track of what is being shared in a directory

- Send point-to-point requests to processors

Shared Memory Architecture

- all processors to access all memory as global address space (UMA, NUMA)

- Advantage

- Global address space provides a user-friendly programming perspective to memory

- Data sharing between tasks is both fast and uniform due to the proximity of memory to CPUs

- Disadvantages

- Primary disadvantage is the lack of scalability between memory and CPUs

- Programmer responsibility for synchronization

- Expense: it becomes increasingly difficult and expensive to design and produce shared memory machines with ever increasing number of processors.

Distributed Memory Architecture

- Characteristics

- Only private(local) memory

- Independent

- require a communication network to connect inter-processor memory

- Advantages

- Scalable (processors, memory)

- Cost effective

- Disadvantages

- Programmer responsibility of data communication

- No global memory access

- Non-uniform memory access time

Hybrid Architecture

- Advantages / Disadvantages

- Combination of Shared/Distributed architecture

- Scalable

- Increased programmer complexity

Ray Tracing

- Shoot a ray into scene through every pixel in image plane

- Follow their paths

- they bounce around as they strike objects

- they generate new rays: ray tree per input ray

- Result is color and opacity for that pixel

- Parallelism across rays

Java Thread Programming

Process

- Operating system abstraction to represent what is needed to run a single program

- a sequential stream of execution in its own address space

- program in execution

- 각 프로세스는 0~ bytes 의 주소를 갖는다. (64비트 운영체제에서)

- 물리적으로는 제한되지만, 논리적으로는 제한이 없는 메모리를 가지고 있을 수 있다.

PCB

- Process Control Block

- 포함하는 것들

- process state

- process number

- program counter

- registers

- memory limits

- list of open files

UNIX process

- Every process, except process 0, is created by the fork() system call

- fork() allocates entry in process table and assigns a unique PID to the child process

- child gets a copy of process image of parent

- both child and parent are executing the same code following fork()

Threads

- Definition

- single sequential flow of control within a program

- A thread runs within the context of a program’s process and takes advantage of the resources allocated for that process and it’s environment

- Each thread is comprised of (from OS perspective)

- Program counter

- Register set

- Stack

- Threads belonging to the same process share

- Code section

- Data section

- OS resources such as open files

Single and multithreaded program

- code, data, files 는 스레드들 사이에서 공유된다.

Multi-process vs Multi-thread

- Process

- Child process gets a copy of parents variables

- Relatively expensive to start

- Don’t have to worry about concurrent access to variables

- Thread

- Child thread shares parent’s variables

- Relatively cheap to start

- Concurrent access to variables is an issue

Programming Java threads

JAVA Threading Models

- Java has threads build-in

- Applications consist of at least one thread

- Often called ‘main’

- The Java Virtual Machine creates the initial thread which executes the main method of the class passed to the JVM

- The methods executed by the ‘main’ thread can then create other threads

Creating Threads : method 1

- A Thread class manages a single sequential thread of control.

class MyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

// work to do

}

}Thread Names

- All threads have a name to be printed out

- The default name is of the format:

Thread-No - User-defined names can be given through constructor

Thread myThread = new Thread(“HappyThread”)

- Or usinig the

setName(aString)method. - There is a method in Thread class, called

getName()to obtain a thread’s name

Creating Threads : method 2

- Since Java does not permit multiple inheritance, we often implement the run() method in a class not derived from Thread from the interface Runnable

public inerface Runnable {

public abstract void run();

}

class MyRun implements Runnable {

public void run() {

// work to do

}

}

Thread t = new Thread(new MyRun());

t.start();Creating & Executing Threads (Runnable)

- Runnable interface has single method

- public void run()

- Implement a Runnable and define run()

- Thread’s run() method invokes the Runnable’s run() method

Thread Life-Cycle

- Created

- start() → Alive

- stop() → Terminated

- Alive

- stop() or run() returns

- Terminated

Alive States

- Once started, an alivethread has a number of substates

- start() → Running

- sleep(), wait() I/O blocking

- yield() → Runnable

- Runnable (Ready)

- dispatch → Running

- Non-Runnable

- notify(), Time expires, I/O completed → Runnable

- start() → Running

Thread Priority

- All Java threads have a priority value, currently between 1 and 10.

- Priority can be changed at any time

- Initial priority is that of the creating thread

- Preemptive scheduling

- JVM gives preference to higher priority threads (Not guaranteed)

yield

- Release the right of CPU

- static void yield()

- allows the scheduler to select another runnable thread (of the same priority)

- no guarantees as to which thread

Thread identity

Thread.currentThread()- Returns reference to the running thread

Thread sleep, suspend, resume

static void sleep(long millis)- Blocks this thread for at least the time specified

void stop(), void suspend(), void resume()- Deprecated!

Thread Waiting & Status Check

void join(), void join(long), void join(long, int)- One thread (A) can wait for another thread (B) to end

boolean isAlive()- returns true if the thread has been started and not stopped

Thread synchronization

- The advantage of threads is that they allow many things to happen at the same time

- The problem with threads is that they allow many things to happen at the same time

- Safety

- Nothing bad ever happens

- no race condition

- Liveness

- Something eventually happens: no deadlock

- Concurrent access to shared data in an object

- Need a way to limit thread’s access to shared data

- Reduce concurrency

- Mutual Exclusion of Critical Section

- Add a lock to an object

- Any thread must acquire the lock before executing the methods

- If lock is currently unavailable, thread will block

Synchronized JAVA methods

- We can control access to an object by using the

synchronizedkeyword - Using the

synchronizedkeywork will force the lock on the object to be used

Synchronized Lock Object

- Every Java object has an associated lock acquired via

- synchronized statements (block)

- Only one thread can hold a lock at a time

- Lock granularity: small critical section is better for concurrency object

Condition Variables

- lock(syncrhonized)

- control thread access to data

- condition variable (wait,notify/notifyall)

- synchronization primitives that enable threads to wait until a particular condition occurs

- enable threads to atomically release a lock and enter the sleeping state.

- Without condition variables

- the programmer would need to have threads continually polling (possibly in a critical section), to check if the condition is met

- A condition variable is a way to achieve the same goal without polling

- A condition variable is always used in conjunction with a mutex lock

wait() and notify()

wait()- If no interrupt (normal case), current thread is blocked

- The thread is placed into wait set associated with the object

- Synchronization lock for the object is released

notify()- One thread, say T, is removed from wait set, if exists.

- T retains the lock for the object

- T is resumed from waiting stauts

Producer-Consumer Problem

- The problem describes two processes, the producer and the consumer, who share a common, fixed-size buffer used as a queue.

- producer: generate a piece of data, put it into the buffer and start again. At the same time,

- consumer: consumes the data (i.e., removing it from the buffer) one piece at a time.

- The problem is to make sure that the producer won't try to add data into the buffer if it's full and that the consumer won't try to remove data from an empty buffer.

- The solution for the producer is to go to sleep if the buffer is full. The next time the consumer removes an item from the buffer, it notifies the producer, who starts to fill the buffer again.

- In the same way, the consumer can go to sleep if it finds the buffer to be empty. The next time the producer puts data into the buffer, it wakes up the sleeping consumer.

- generalized to have multiple producers and consumers.

To motivate condition variables, consider the canonical example of a bounded buffer for sharing work among threads

Bounded buffer: A queue with a fixed size

- (Unbounded still needs a condition variable, but 1 instead of 2)

For sharing work – think an assembly line:

- Producer thread(s) do some work and enqueue result objects

- Consumer thread(s) dequeue objects and do next stage

- Must synchronize access to the queue

Waiting

- enqueue to a full buffer should not raise an exception

- Wait until there is room

- dequeue from an empty buffer should not raise an exception

- Wait until there is data

What we want

- Better would be for a thread to wait until it can proceed

- Be notified when it should try again

- In the meantime, let other threads run

- Like locks, not something you can implement on your own

- Language or library gives it to you, typically implemented with operating-system support

- An ADT that supports this: condition variable

- Informs waiter(s) when the condition that causes it/them to wait has varied

- Terminology not completely standard; will mostly stick with Java

Key ideas

- Java weirdness: every object “is” a condition variable (and a lock)

- other languages/libraries often make them separate

- wait:

- “register” running thread as interested in being woken up

- then atomically: release the lock and block

- when execution resumes, thread again holds the lock

- notify:

- pick one waiting thread and wake it up

- no guarantee woken up thread runs next, just that it is no longer blocked on the condition – now waiting for the lock

- if no thread is waiting, then do nothing

Bug 1

Between the time a thread is notified and it re-acquires the lock, the condition can become false again!

Guideline: Always re-check the condition after re-gaining the lock

- In fact, for obscure reasons, Java is technically allowed to notify a thread spuriously (i.e., for no reason)

Bug 2

- If multiple threads are waiting, we wake up only one

- Sure only one can do work now, but can’t forget the others!

notifyAll wakes up all current waiters on the condition variable Guideline: If in any doubt, use notifyAll

- Wasteful waking is better than never waking up

- So why does notify exist?

- Well, it is faster when correct…

Java Multithread Programming Exercise

class C extends Thread {

int i;

C(int i) { this.i = i; }

public void run() {

System.out.println("Thread " + i + " says hi");

try {

sleep(500);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {}

System.out.println("Thread " + i + " says bye");

}

}

public class ex1 {

private static final int NUM_THREAD = 10;

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("main thread start!");

C[] c = new C[NUM_THREAD];

for(int i=0; i < NUM_THREAD; ++i) {

c[i] = new C(i);

c[i].start();

}

System.out.println("main thread calls join()!");

for(int i=0; i < NUM_THREAD; ++i) {

try {

c[i].join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {}

}

System.out.println("main thread ends!");

}

}public class ex2_serial {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] int_arr = new int [10000];

int i,s;

for (i=0;i<10000;i++) int_arr[i]=i+1;

s=sum(int_arr);

System.out.println("sum=" + s +"\n");

}

static int sum(int[] arr) {

int i;

int s=0;

for (i=0;i<arr.length;i++) s+=arr[i];

return s;

}

}class SumThread extends Thread {

int lo; // fields for communicating inputs

int hi;

int[] arr;

int ans = 0; // for communicating result

SumThread(int[] a, int l, int h) {

lo=l; hi=h; arr=a;

}

public void run() { // overriding, must have this type

for(int i=lo; i<hi; i++)

ans += arr[i];

}

}

class ex2 {

private static int NUM_END=10000;

private static int NUM_THREAD=4;

public static void main(String[] args) {

if (args.length==2) {

NUM_THREAD = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

NUM_END = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

}

System.out.println("number of threads:"+NUM_THREAD);

System.out.println("sum from 1 to "+NUM_END+"=");

int[] int_arr = new int [NUM_END];

int i,s;

for (i=0;i<NUM_END;i++) int_arr[i]=i+1;

s=sum(int_arr);

System.out.println(s);

}

static int sum(int[] arr) {

int len = arr.length;

int ans = 0;

SumThread[] ts = new SumThread[NUM_THREAD];

for(int i=0; i < NUM_THREAD; i++) {

ts[i] = new SumThread(arr,(i*len)/NUM_THREAD,((i+1)*len)/NUM_THREAD);

ts[i].start();

}

try {

for(int i=0; i < NUM_THREAD; i++) {

ts[i].join();

ans += ts[i].ans;

}

} catch (InterruptedException IntExp) {

}

return ans;

}

}ex2 는 naive 한 solution 이다. 결국은 thread 개수만큼 for 문을 돌면서 더해줘야 하기 때문이다.

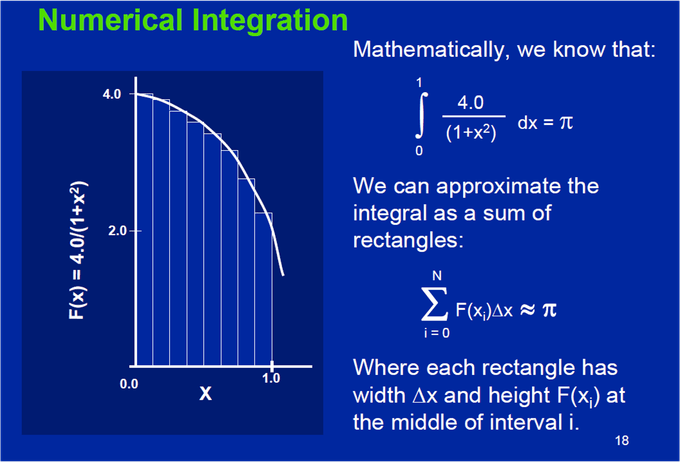

class IntThread extends Thread {

int my_id; // fields for communicating inputs

int num_steps;

int num_threads;

double sum;

IntThread(int id, int numSteps, int numThreads) {

my_id=id; num_steps=numSteps; num_threads=numThreads;

sum=0.0;

}

public void run() {

double x;

int i;

int i_start = my_id * (num_steps/num_threads);

int i_end = i_start + (num_steps/num_threads);

double step = 1.0/(double)num_steps;

for (i=i_start;i<i_end;i++) {

x=(i+0.5)*step;

sum=sum+4.0/(1.0+x*x);

}

sum = sum*step;

System.out.println("myid"+my_id+", sum=" + sum);

}

public double getSum() { return sum; }

}

class ex3 {

private static int NUM_THREAD = 4;

private static int NUM_STEP = 1000000000;

public static void main(String[] args) {

int i;

double sum=0.0;

if (args.length==2) {

NUM_THREAD = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

NUM_STEP = Integer.parseInt(args[1]);

}

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

IntThread[] ts = new IntThread[NUM_THREAD];

for(i=0; i < NUM_THREAD; i++) {

ts[i] = new IntThread(i,NUM_STEP,NUM_THREAD);

ts[i].start();

}

try {

for (i=0;i<NUM_THREAD;i++) {

ts[i].join();

sum += ts[i].getSum();

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {}

long finish = System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("integration result=" + sum +"\n");

System.out.println("Execution time (" + NUM_THREAD + "): "+(finish-start)+"ms");

}

}Parallelism for summation

-

Example: Sum elements of a large array

-

Idea: Have 4 threads simultaneously sum 1/4 of the array

- Warning: This is an inferior first approach

-

Create 4 thread objects, each given a portion of the work

-

Call start() on each thread object to actually run it in parallel

-

Wait for threads to finish using join()

-

Add together their 4 answers for the final result

-

Problems? : processor utilization, subtask size

A better Approach

Solution is to use lots of threads, far more than the number of processors

- reusable and efficient across platforms

- Use processors “available to you now” :

- Hand out “work chunks” as you go

- Load balance

- in general subproblems may take significantly different amounts of time

Naive algorithm is poor

Suppose we create 1 thread to process every 1000 elements

Then combining results will have arr.length / 1000 additions

- Linear in size of array (with constant factor 1/1000)

- Previously we had only 4 pieces (constant in size of array)

In the extreme, if we create 1 thread for every 1 element, the loop to combine results has length-of-array iterations

- Just like the original sequential algorithm

A better idea: devide-and-conquer

This is straightforward to implement using divide-and-conquer

- Parallelism for the recursive calls

- The key is divide-and-conquer parallelizes the result-combining

- If you have enough processors, total time is height of the tree: O(log n) (optimal, exponentially faster than sequential O(n))

- We will write all our parallel algorithms in this style

class SumThread extends java.lang.Thread {

int lo; int hi; int[] arr; // arguments

int ans = 0; // result

SumThread(int[] a, int l, int h) { … }

public void run(){ // override

if(hi – lo < SEQUENTIAL_CUTOFF)

for(int i=lo; i < hi; i++)

ans += arr[i];

else {

SumThread left = new SumThread(arr,lo,(hi+lo)/2);

SumThread right= new SumThread(arr,(hi+lo)/2,hi);

left.start();

right.start();

left.join(); // don’t move this up a line – why?

right.join();

ans = left.ans + right.ans;

}

}

}

int sum(int[] arr){

SumThread t = new SumThread(arr,0,arr.length);

t.run();

return t.ans;

}Being realistic

- In theory, you can divide down to single elements, do all your result-combining in parallel and get optimal speedup

- Total time O(n/numProcessors + log n)

- In practice, creating all those threads and communicating swamps the savings, so:

- Use a sequential cutoff, typically around 500-1000

- Eliminates almost all the recursive thread creation (bottom levels of tree)

- Exactly like quicksort switching to insertion sort for small subproblems, but more important here

- Do not create two recursive threads; create one and do the other “yourself”

- Cuts the number of threads created by another 2x

- Use a sequential cutoff, typically around 500-1000

Concurrent Programming

What is concurrency?

- What is a sequential program?

- A single thread of control that executes one instruction and when it is finished execute the next logical instruction

- What is a concurrent program?

- A collection of autonomous sequential threads, executing (logically) in parallel

- The implementation of a collection of threads can be:

- Multiprogramming

- Threads multiplex their executions on a single processor

- Multiprocessing

- Threads multiplex their executions on a multiprocessor or a multicore system

- Distributed Processing

- Processes multiplex their executions on several different machines

- Multiprogramming

Concurrency and Parallelism

- Concurrency is not parallelism

- Interleaved Concurrency

- Logically simultaneous processing

- Interleaved execution on a single processor

- Parallelism

- Physically simultaneous processing

- Requires a multiprocessors or a multicore system

Why use Concurrent Programming?

- Natural Application Structure

- The world is not sequential! Easier to program multiple independent and concurrent activities.

- Increased application throughput and responsiveness

- Not blocking the entire application due to blocking I/O

- Performance from multiprocessor/multicore hardware

- Parallel execution

- Distributed systems

- Single application on multiple machines

- Client/Server type or peer-to-peer systems

Synchronization

- All the interleavings of the threads are NOT acceptable correct programs

- Java provides synchronization mechanism to restrict the interleavings

- Synchronization serves two purposes:

- Ensure safety for shared updates

- Avoid race conditions

- Coordinate actions of threads

- Parallel computation

- Event notification

- Ensure safety for shared updates

Safety

- Multiple threads access shared resource simultaneously

- Safe only if:

- All accesses have no effect on resource,

- All accesses idempotent

- Only one access at a time: mutual exclusion

Mutual Exclusion

- Prevent more than one thread from accessing critical section at a given time

- Once a thread is in the critical section, no other thread can enter that critical section until the first thread has left the critical section

- No interleavings of threads within the critical section

- Serializes access to section

Atomicity

- Synchronized methods execute the body as an atomic unit

- May need to execute a code region as the atomic unit

- Block Synchronization is a mechanism where a region of code can be labeled as synchronized

- The synchronized keyword takes as a parameter an object whose lock the system needs to obtain before it can continue

Avoiding Deadlock

- Cycle in locking graph = deadlock

- Standard solution: canonical order for locks

- Acquire in increasing order

- Release in decreasing order

- Ensures deadlock-freedom, but not always easy to do

Races

- Race conditions - insidious bugs

- Non-deterministic, timing dependent

- Cause data corruption, crashes

- Difficult to detect, reproduce, eliminate

- Many programs contain races

- Inadvertent programming errors

- Failure to observe locking displine

Data Races

- A data race happens when two threads access a variable simultaneously, and one access is a write

- Problem with data races: non-determinism

- Depends on interleaving of threads

- Usual way to avoid data races: mutual exclusion

- Ensures serialized access of all the shared objects

Potential Concurrency Problems

- Deadlock

- Two or more threads stop and wait for each other

- Livelock

- Two or more threads continue to execute, but make no progress toward the ultimate goal.

- Starvation

- Some thread gets deffered forever.

- Lack of fairness

- Each thread gets a turn to make progress.

- Race Condition

- Some possible interleaving of threads results in an undesired computation result

Important Concepts in Concurrent Programming (from wikipedia)

- Concurrency / Parallelism: logically / physically simultaneous processing

- Synchronization

- coordication of simultaneous events (threads / processes) in order to obtain correct run time order and void unexpected race condition.

- Mutual Exclusion

- ensuring that no two processes ro threads are in their critical section at the same time

- Critical Section

- a piece of code that accesses a shared resource (data structure or device) that must not be concurrently accessed by more than one thread of execution

- Race Condition

- a type of flaw in an electronic or software system where the output is dependent on the sequence or timing of other uncontrollable events.

- Semaphore

- a synchronization object that maintains a count between zero and a specified maximum value. The count is decremented each time a thread completes a wait for the semaphore object and incremented each time a thread releases the semaphore. When the count reaches zero, no more threads can successfully wait for the semaphore object state to become signaled.

- concurrent hash map

- a hash table supporting full concurrency of retrievals and adjustable expected concurrency for updates.

- copy on write arrays

- CopyOnWriteArrayList behaves as a List implementation that allows multiple concurrent reads, and for reads to occur concurrently with a write. The way it does this is to make a brand new copy of the list every time it is altered.

- Barrier

- a type of synchronization method. A barrier for a group of threads or processes in the source code means any thread/process must stop at this point and cannot proceed until all other threads / processes reach this barrier.

Pthread Programming

What is Thread?

- Independent stream of instructions executed simultaneously by OS

- Multithreaded program

- A main program contains a number of procedures that are scheduled to run simultaneously and independently by OS

Processes and Threads

- Threads share resources of a process

- Changes made by one thread affect other threads

- Two pointers having the same value point to the same data

- Reading and writing to the same memory location is possible

- Processes don’t share resources

Thread Properties

- Exists within a process and uses the process resources

- Has its own independent flow of control as long as its parent process exists and the OS supports it.

- Duplicates only the essential resources it needs to be independently schedulable (like stack, register)

- May share the process resources with other threads that act equally independently

- Dies if the parent process dies - or something similar

- Is “lightweight” because most of the overhead has already been accomplished through the creation of its process

- All threads within a process share same address space

- Therefore, inter-thread communication is more efficient than inter-process communication

pthread

-

POSIX thread

-

Standardized C language threads for UNIX

-

For portability

-

Working in shared memory multiprocessor

-

Why pthreads?

- Performance gains

- Requires fewer system resources than process

- compare fork() and pthread_create(): 10~50 times

Pthreads API

- Thread Management

- Thread creation, and destruction

- Mutexes

- synchronization

- Conditional Variables

- Communication between threads that share a mutex

Thread Creation

int pthread_create(

pthread_t *restrict thread,

const pthread_attr_t *restrict attr,

void *(*start_routine) (void *),

void *restrict arg

);-

Creates a new thread and makes it executable

-

The creating process (or thread) must provide a location for storage of thread id

-

The third parameter is just the name of the function for the thread to run

-

The last parameter is a pointer to the arguments

-

When a new thread is created, it runs concurrently with the creating process.

-

When creating a thread, you indicate which function the thread should execute

-

Thread handle returned via

pthread_tstructure -

Specify

NULLto use default attributes -

Single argument sent to the function

-

If no arguments to function, specify

NULL -

Check error codes!

-

[i] Example

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <stdio.h>

long OddSum=0;

long EvenSum=0;

void findEven(long start, long end)

{

for (long i=start;i<=end;i++) if ((i&1)==0) EvenSum += i;

}

void findOdd(long start, long end)

{

for (long i=start;i<=end;i++) if ((i&1)==1) OddSum += i;

}

// Functor (Function Object)

class FindOddFunctor {

public:

void operator()(int start, int end) {

for (int i=start;i<=end;i++) if ((i&1)==1) OddSum += i;

}

};

// class member function

class FindOddClass {

public:

void myrun(int start, int end) {

for (int i=start;i<=end;i++) if ((i&1)==1) OddSum += i;

}

};

int main()

{

long start = 0, end = 1000;

std::thread t1(findEven, start, end);

//std::thread t2(findOdd, start, end); // (method 1) create thread using function pointer

//FindOddFunctor findoddfunctor;

//std::thread t2(findoddfunctor, start, end); // (method 2) create thread using functor

//FindOddClass oddObj;

//std::thread t2(&FindOddClass::myrun, &oddObj, start, end); // (method 3) create thread using member function of an object

// (method 4) create thread using lambda function

std::thread t2([&](long s, long e) {

for (long i=s;i<=e;i++) if ((i&1)==1) OddSum += i;

}, start, end);

t1.join(); // wait until thread t1 is finished.

t2.join(); // wait until thread t2 is finished.

//t2.detach(); // continue to run without waiting

std::cout << "OddSum: " << OddSum << std::endl;

std::cout << "EvenSum: " << EvenSum << std::endl;

return 0;

}Thread Termination

void pthread_exit(void *value_ptr)

- There are several ways in which a pthread may be terminated

- The thread returns from its starting routine (the main routine for the initial thread)

- The thread makes a call to the

pthread_exitsubroutine - The thread is canceled is terminated due to making a call to either the

exec()orexit() - If main() finishes first, without calling

pthread_exitexplicitly itself

- Typically, the pthread_exit() routine is called to quit the thread

- If main() finishes before the threads it has created, and exits with pthread_exit(), the other threads will continue to execute. Otherwise, they’ll be automatically terminated when main() finishes.

- The programmer may optionally specify a termination status, which is stored as a void pointer for any thread that may join the calling thread

- Cleanup: the pthread_exit() routine does not close files; any files opened inside the thread wil remain open after the thread is terminated.

Thread Cancellation

- One thread can request that another exit with pthread_cancel

int pthread_cancel(pthread_t thread)- The pthread_cancel returns after making the request

Joining

int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **value_ptr)

- The pthread_join() subroutine blocks the calling thread until the specified thread terminates

- The programmer is able to obtain the target thread’s termination return status if it was specified in the target thread’s call to pthread_exit()

- A joining thread can match one pthread_join() call. It is a logical error to attempt multiple joins on the same thread

Mutexes

- Mutual Exclusion

- implementing thread synchronization and protecting shared data when multiple writes occur

- A mutex variable acts like a “lock” protecting access to a shared data resource

- only one thread can lock a mutex variable at any given time

- Used for preventing race condition

- When several threads compete for a mutex, the losers block at that call - an unblocking call is available with

trylockinstead of thelockcall

Mutex Routines

pthread_mutex_init (mutex, attr)

pthread_mutex_destroy(mutex)

- Mutex variables must be declared with type

pthread_mutex_t, and must be initialized before they can be used.

Locking / Unlocking Mutexes

pthread_mutex_lock(mutex)- acquire a lock on the specified mutex variable

pthread_mutex_trylock(mutex)- attempt to lock a mutex. However, if the mutex is already locked, the routine will return immediately with a “busy” error code

pthread_mutex_unlock(mutex)- unlock a mutex if called by the owning thread

User’s Responsibility for Using Mutex

- When protecting shared data, it is the programmer’s responsibility to make sure every thread that needs to use a mutex does so

- For example, if 3 threads are updating the same data, but only one or two use a mutex, the data can still be corrupted

Condition Variables

- another way for threads to synchronize

- mutexes

- synchronization by controlling thread access to data

- condition variables

- synchronization based upon the actual value of data

- Without condition variables, the programmer would need to have threads continually polling (possibly in a critical section), to check if the condition is met

- always used in conjunction with a mutex lock

Condition Variables Routines

pthread_cond_init(condition, attr)

pthread_cond_destroy(condition)

- Condition variables must be declared with type

pthread_cond_t, and must be initialized before they can be used - attr is used to set condition variable attributes (NULL: defaults)

pthread_cond_destroy()should be used to free a condition variable that is no longer neededpthread_cond_wait- blocks the calling thread until the specified condition is signalled

- This routine should be called while mutex is locked

- will automatically release the mutex lock while it waits

- After signal is received and thread is awakened, mutex will be automatically locked for use

pthread_cond_signal(condition)- signal (or wake up) another thread which is waiting on the condition variable

- It is a logical error to call pthread_cond_signal() before calling pthread_cond_wait()

pthread_cond_broadcast(condition)- should be used instead of pthread_cond_signal() if more than one thread is in a blocking wait state

C++ Multithreaded Programming

C++ Multi-Threading

- C++11

- First C++ standard that introduced threads, mutexes (locks), conditional variables etc

- C++17

- Parallel STL: addition of parallel algorithms in STL

C++ Thread Library

- include header file

<thread> - Create and starts a new thread using

std::thread- Syntax:

thread(func, args…) funcwill be called in a new thread- The new thread will terminate when

funcreturns - All parameters passed to

funcare passed by value - For pass by reference, wrap them in

std::ref

- Syntax:

- 4 ways to create a thread in C++

- using function pointer

- using functor (function object)

- using class member function

- using lambda expression

- Call the member function

join()to wait for a thread to finish - Call the member function

detach()to run independently- No join: join is not allowed after calling detach()

- If thread object is destructed without calling detach(), error might occur

- After a call to this function, the thread object becomes non-joinable and can be destroyed safely

- The parent thread should call

join()ordetach() - Include header file

<mutex>to usestd::mutexstd::lock_guard: locks a supplied mutex on construction and unlocks it on destruction (simple exclusive lock)

std::atomicfor atomic variables- operations are atomic

- behave as if it is inside a mutex-protected critical section

- usually faster than mutex lock (HW supported)

Parallel STL

- C++ STL algorithms with support for execution policies (C++17 or later)

- Execution Policy

Stl_function(execution_policy, ... other_arguments ...);std::execution::seq- 1 thread, sequential

std::execution::par- multiple threads

std::execution::par_unseq- multiple threads, SIMD (vectorization) possible

std::execution::unseq- 1 thread, SIMD (vectorization) possible

Example

- clock_lock

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

int inc_num=10001234;

int dec_num=10000000;

std::mutex m;

class CountLock {

int count;

public:

CountLock() : count(0) {}

int getCount()

{

int val;

m.lock();

val = count;

m.unlock();

return val;

}

void inc()

{

m.lock();

count++;

m.unlock();

}

void dec()

{

m.lock();

count--;

m.unlock();

}

};

class Producer

{

CountLock& c_lock;

public:

Producer(CountLock& clock): c_lock(clock) {

}

void run() {

for (int i=0;i<inc_num;i++) c_lock.inc();

}

};

class Consumer

{

CountLock& c_lock;

public:

Consumer(CountLock& clock): c_lock(clock) {

}

void run() {

for (int i=0;i<dec_num;i++) c_lock.dec();

}

};

int main()

{

CountLock count_lock;

Producer p(count_lock);

Consumer c(count_lock);

std::thread threadP(&Producer::run,&p);

std::thread threadC(&Consumer::run,&c);

threadP.join();

threadC.join();

std::cout<<"after main join count:"<<count_lock.getCount()<<std::endl;

return 0;

}- clock_atomic

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include <atomic>

int inc_num=10001234;

int dec_num=10000000;

class CountLock {

std::atomic<int> count;

public:

CountLock() : count(0) {}

int getCount()

{

return count;

}

void inc()

{

count++;

}

void dec()

{

count--;

}

};

class Producer

{

CountLock& c_lock;

public:

Producer(CountLock& clock): c_lock(clock) {

}

void run() {

for (int i=0;i<inc_num;i++) c_lock.inc();

}

};

class Consumer

{

CountLock& c_lock;

public:

Consumer(CountLock& clock): c_lock(clock) {

}

void run() {

for (int i=0;i<dec_num;i++) c_lock.dec();

}

};

int main()

{

CountLock count_lock;

Producer p(count_lock);

Consumer c(count_lock);

std::thread threadP(&Producer::run,&p);

std::thread threadC(&Consumer::run,&c);

threadP.join();

threadC.join();

std::cout<<"after main join count:"<<count_lock.getCount()<<std::endl;

return 0;

}- psort.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <ctime>

#include <execution>

int main()

{

std::vector<int> vec(100000000);

// fill vector with random numbers

std::srand(unsigned(std::time(nullptr)));

std::generate(vec.begin(), vec.end(), std::rand);

auto start_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::sort(vec.begin(), vec.end());

auto end_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto time_diff = end_time - start_time;

std::cout << "sorting time: " <<

time_diff / std::chrono::milliseconds(1) << "ms to run.\n";

std::srand(unsigned(std::time(nullptr)));

std::generate(vec.begin(), vec.end(), std::rand);

start_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::sort(std::execution::par, vec.begin(), vec.end());

end_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

time_diff = end_time - start_time;

std::cout << "parallel sorting time: " <<

time_diff / std::chrono::milliseconds(1) << "ms to run.\n";

system("pause");

return 0;

}- ptransform.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <ctime>

#include <execution>

bool isPrime(int x)

{

int i;

if (x <= 1) return false;

for (i = 2; i < x; i++) {

if (x % i == 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

int getPrimeNo(int n)

{

int i;

int prime_count = 0;

for (i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

if (isPrime(i)) prime_count++;

}

std::cout << "No. of Primes (" << n << ") =" << prime_count << "\n";

return prime_count;

}

int main()

{

int i;

std::vector<int> A = { 100000, 100100, 100200, 100300, 100400, 100500, 100600, 100700, 100800, 100900,

101000, 101100, 101200, 101300, 101400, 101500, 101600, 101700, 101800, 101900 };

std::vector<int> B;

B.resize(A.size());

auto start_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::transform(A.begin(), A.end(), B.begin(), getPrimeNo);

auto end_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto time_diff = end_time - start_time;

std::cout << "transform time:" << time_diff / std::chrono::milliseconds(1) << "ms\n";

for (i = 0; i < B.size(); i++) std::cout << B[i] << "\n";

start_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::transform(std::execution::par, A.begin(), A.end(), B.begin(), getPrimeNo);

end_time = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

time_diff = end_time - start_time;

std::cout << "parallel transform time:" << time_diff / std::chrono::milliseconds(1) << "ms\n";

for (i = 0; i < B.size(); i++) std::cout << B[i] << "\n";

system("pause");

return 0;

}OpenMP

Background

- OpenMP is a framework for shared memory parallel computing

- OpenMP is a standard C/C++ and Fortran compilers

- Compiler directives indicate where parallelism should be used

- C/C++ use

#pragmadirectives - Fortran uses structured comments

- C/C++ use

- A library provides support routines

- Based on the fork / join model:

- the program starts as a single thread

- at designated parallel regions a pool of threads is formed

- the threads execute in parallel across the region

- at the end of the region the threads wait for all of the team to arrive

- the master thread continues until the next parallel region

- Some advantages

- Usually can arrange so the same code can run sequentially

- Can add parallelism incrementally

- Compiler can optimize

- The OpenMP standard specifies support for C/C++ and Fortran

- Many compilers now support OpenMP

- The OpenMP runtime creates and manages separate threads

- OpenMP is much easier to use than low level thread libraries

- You still have to make sure what you are donig is thread-safe

Some OMP Library Functions

- The OMP library provides a number of useful routines

- Some of the most commonly used

omp_get_thread_num: current thread indexomp_get_num_threads: size of the active teamomp_get_max_threads: maximum number of threadsomp_get_num_procs: number of processors availableomp_get_wtime: elapsed wall clock time from “some time in the past”omp_get_wtick: timer resolution

Parallel Loops in OpenMP

- OpenMP provides directives to support parallel loops

#pragma omp parallel

#pragma omp for

for (i = 0; i<n; i++)#pragma omp parallel for

for (i = start; i<end; i++)- There are some restrictions on the loop, including

- The loop has to be of this simple form with

- start and end computable before the loop

- a simple comparison test

- a simple increment or decrement expression

- exits with

bread,goto,returnare not allowed

- The loop has to be of this simple form with

Shared and Private Variables

- Variables declared before a prallel block can be shared or private

- Shared variables are shared among all threads

- Private variables vary independently within threads

- On entry, values of private variables are undefined

- On exit, values of private variables are undefined

- By default,

- all varaibles declared outside a parallel block are shared

- except the loop index variable, which is private

- Variables declared in a prallel block are always private

- Variables can be explicitly declared shared or private

- A simple example

#pragma omp parallel for

for (i = 0; i<n; i++)

x[i] = x[i] + y[i];- Here x, y, and n are shared an i is private in the parallel loop

- We can make the attributes explicit with

#pragma omp parallel for shared(x, y, n) private (i)

for (i = 0; i<n; i++) {

x[i] = x[i] + y[i];

}

or

#pragma omp parallel for default(shared) private (i)

for (i = 0; i<n; i++) {

x[i] = x[i] + y[i];

}- The value of i is undefined after the loop

Critical Sections and Reduction Variables

int sum = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for

for(i = 0; i<n; i++) {

int val = f(i);

sum = sum + val;

}- Problem: there is a race condition in the updating of sum

- One solution is to use a critical section

int sum = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for

for(i = 0; i<n; i++) {

int val = f(i);

#pragma omp critical

sum = sum + val;

}- Only one thread at a time is allowed into a critical section

- An alternative is to use a reduction variable

int sum = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:sum)

for(i = 0; i<n; i++) {

int val = f(i);

sum = sum + val;

}- Reduction variables are in between private and shared variables

- Other supported reduction operators include

*, &&, and ||

Some Additional Clauses

firstprivatelastprivatedeclare variables privatefirstprivatevariables are initialized to their value before the parallel section- For

lastprivatevariables the value of the variable after the loop is the value after the logically last iteration - Variables can be listed both as

firstprivateandlastprivate - The

ifclause can be used to enable parallelization conditionally num_threads(p)says to usePthreadsschedule(static, n)divides the loop into chunks of size n assigned cyclically to the threadsschedule(dynamic, n)divides the loop into chunks of size n assigned cyclically to the next available thread

The parallel region

- A parallel region is a block of code executed by multiple threads simultaneously

#pragma omp parallel [clause ...]

{

"this will be executed in parallel"

} (implied barrier)

!$omp parallel [clause ...]

"this will be executed in parallel"

!$omp end parallelThe parallel region - clauses

- A parallel region supports the following clauses

- if

- private

- shared

- default

- reduction

- copyin

- firstprivate

- num_threads

Work-sharing constructs

#pragma omp for

{

}

#pragma omp sections

{

}

#pragma omp single

{

}- The work is distributed over the threads

- Must be enclosed in a prallel region

- Must be encountered by all threads in the team, or none at all

- No implied barrier on entry; implied barrier on exit (unless nowait is specified)

- A work-sharing construct does not launch any new threads

Load balancing

- Load balancing is an important aspect of performance

- For regular operations, load balancing is not a issue

- For less regular workloads, care needs to be taken in distributing the work over the threads

- Examples of irregular workloads

- Transposing a matrix

- Multiplication of triangular matrices

- Parallel searches in a linked list

- For these irregular situations, the schedule clause supports various iteration scheduling algorithms

The schedule clause / 1

static [, chunk]- Distribute iterations in blocks of size “chunk” over the threads in a round-robin fashion

- In absence of chunk, each thread executes approx. N/P chunks for a loop of length N and P threads

dynamic [, chunk]- Fixed portions of work; size is controlled by the value of chunk

- When a thread finishes, it starts on the next portion of work

guided [, chunk]- Same dynamic behaviour as “dynamic”, but size of the portion of work decreases exponentially

runtime- Iteration scheduling scheme is set at runtime through environment variable`OMP_SCHEDULE

The SECTIONS directive

- The individual code blocks are distributed over the threads

#pragma omp sections [clauses]

{

#pragma omp section

<code block1>

#pragma omp section

<code block2>

...

}- Clauses supported

- private

- firstprivate

- lastprivate

- reduction

- nowait

Barrier

- We need to have updated all of a first, before using a

- Each thread waits until all others have reached this point

#pragma omp barrier

Critical region

- If sum is a shared variable, this loop can not be run in parallel

- All threads execute the code, but only one at a time

#pragma omp critical [(name)]#pragma omp atomic- This is a lightweight, special form of a critical section

SINGLE and MASTER construct

- Only one thread in the team executes the code enclosed

#pragma omp single [clauses ...]

{

<code-block>

}- Only master thread executes the code block:

#pragma omp master

{code block}- There is no implied barrier on entry or exit

pi computation

OpenMP

#include <omp.h>

#include <stdio.h>

long num_steps = 1000000000;

double step;

void main ()

{

long i; double x, pi, sum = 0.0;

double start_time, end_time;

start_time = omp_get_wtime();

step = 1.0/(double) num_steps;

for (i=0;i< num_steps; i++){

x = (i+0.5)*step;

sum = sum + 4.0/(1.0+x*x);

}

pi = step * sum;

end_time = omp_get_wtime();

double timeDiff = end_time - start_time;

printf("Execution Time : %.10lfsec\n", timeDiff);

printf("pi=%.10lf\n",pi);

}pthread

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

#define num_steps 100000

double pi[NUM_THREADS];

void *run(void *threadid) {

int* t_ptr=(int*)threadid;

double step;

double x, sum = 0.0;

int my_id, i;

int i_start = 0, i_end = 0;

my_id = *t_ptr;

i_start = my_id * (num_steps / NUM_THREADS);

i_end = i_start + (num_steps / NUM_THREADS);

step = 1.0 / (double)num_steps;

for (i = i_start; i < i_end; i++) {

x = (i + 0.5)*step;

sum = sum + 4.0 / (1.0 + x*x);

}

printf("Myid%d, sum=%.8lf\n", my_id, sum*step);

pi[my_id] = sum*step;

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

pthread_t threads[NUM_THREADS];

int t, pro_i, status;

int ta[NUM_THREADS];

for (t = 0; t < NUM_THREADS; t++){

ta[t]=t;

pro_i = pthread_create(&threads[t], NULL, run, (void *)&ta[t]);

if (pro_i) {

printf("ERROR code is %d\n", pro_i);

exit(-1);

}

}

int i;

for (i=0;i<NUM_THREADS;i++)

pthread_join(threads[i], (void **)&status);

double pi_sum=0;

for (i=0;i<NUM_THREADS;i++) pi_sum = pi_sum + pi[i];

printf("integration result=%.8lf\n", pi_sum);

pthread_exit(NULL);

}Matrix Calculation

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

#define NX 1000

#define NM NX

#define NY NX

int a[NX * NM];

int b[NM * NY];

int m[NX * NY];

#define A(i, n) a[(i) + NX * (n)]

#define B(n, j) b[(n) + NM * (j)]

#define M(i, j) m[(i) + NX * (j)]

void printMatrix(int* mat, int X, int Y)

{

int i,j;

for (j=0;j<Y;j++) {

for (i=0;i<X;i++) {

printf("%4d ",mat[i+j*X]);

}

printf("\n");

}

}

int main()

{

int i, j, n;

double t1,t2;

/* Initialize the Matrix arrays */

omp_set_num_threads(NUM_THREADS);

t1=omp_get_wtime();

#pragma omp parallel for default(shared) private(n, i)

for (n = 0; n < NM; n++) {

for (i = 0; i < NX; i++) {

A(i, n) =3;

}

}

#pragma omp parallel for default(shared) private(n, j)

for (j = 0; j < NY; j++) {

for (n = 0; n < NM; n++) {

B(n, j) = 2;

}

}

#pragma omp parallel for default(shared) private(i, j)

for (j = 0; j < NY; j++) {

for (i = 0; i < NX; i++) {

M(i, j) = 0;

}

}

/* Matrix-Matrix Multiplication */

#pragma omp parallel for default(shared) private(i, j, n)

for (j = 0; j < NY; j++) {

for (n = 0; n < NM; n++) {

for (i = 0; i < NX; i++) {

M(i, j) += A(i, n) * B(n, j);

}

}

}

t2=omp_get_wtime();

//printMatrix(m,NX,NY);

printf("computation time:%lf, using %d threads\n",t2-t1,NUM_THREADS);

return 0;

}Schedule

#include <omp.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

#define END_NUM 20

int main ()

{

int i;

double start_time, end_time;

omp_set_num_threads(NUM_THREADS);

start_time = omp_get_wtime( );

#pragma omp parallel for schedule(static,2)

//#pragma omp parallel for schedule(dynamic, 2)

//#pragma omp parallel for schedule(guided, 2)

for (i = 1; i <= END_NUM; i++) {

printf("%3d -- (%d/%d)\n",i, omp_get_thread_num(),omp_get_num_threads());

}

end_time = omp_get_wtime( );

printf("time elapsed: %lfs\n",end_time-start_time);

return 0;

}Merge Sort

- Serial Merge Sort

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <omp.h>

#define SWAP(a,b) {int temp = a; a = b; b = temp;}

#define SIZE (1<<16)

void setUp(int a[], int size);

void tearDown(double start, double end, int a[], int size);

void merge(int a[], int size, int temp[]);